Nestled in the heart of Arizona’s Navajo Nation, Antelope Canyon is a mesmerizing slot canyon renowned for its narrow passageways, undulating sandstone walls, and ethereal beams of light that seem almost otherworldly. But what makes this canyon truly extraordinary? Is it the way sunlight pierces through the narrow openings to create dancing beams on the smooth, flowing walls? Or is it the sense of stepping into a secret world carved over millions of years by water and wind? Beyond its breathtaking visuals, Antelope Canyon carries stories of ancient geological forces and deep Navajo cultural significance. Its allure is more than just scenery—it is a place where nature, history, and spirituality converge, inviting every visitor to uncover its hidden mysteries.

The Formation of Antelope Canyon

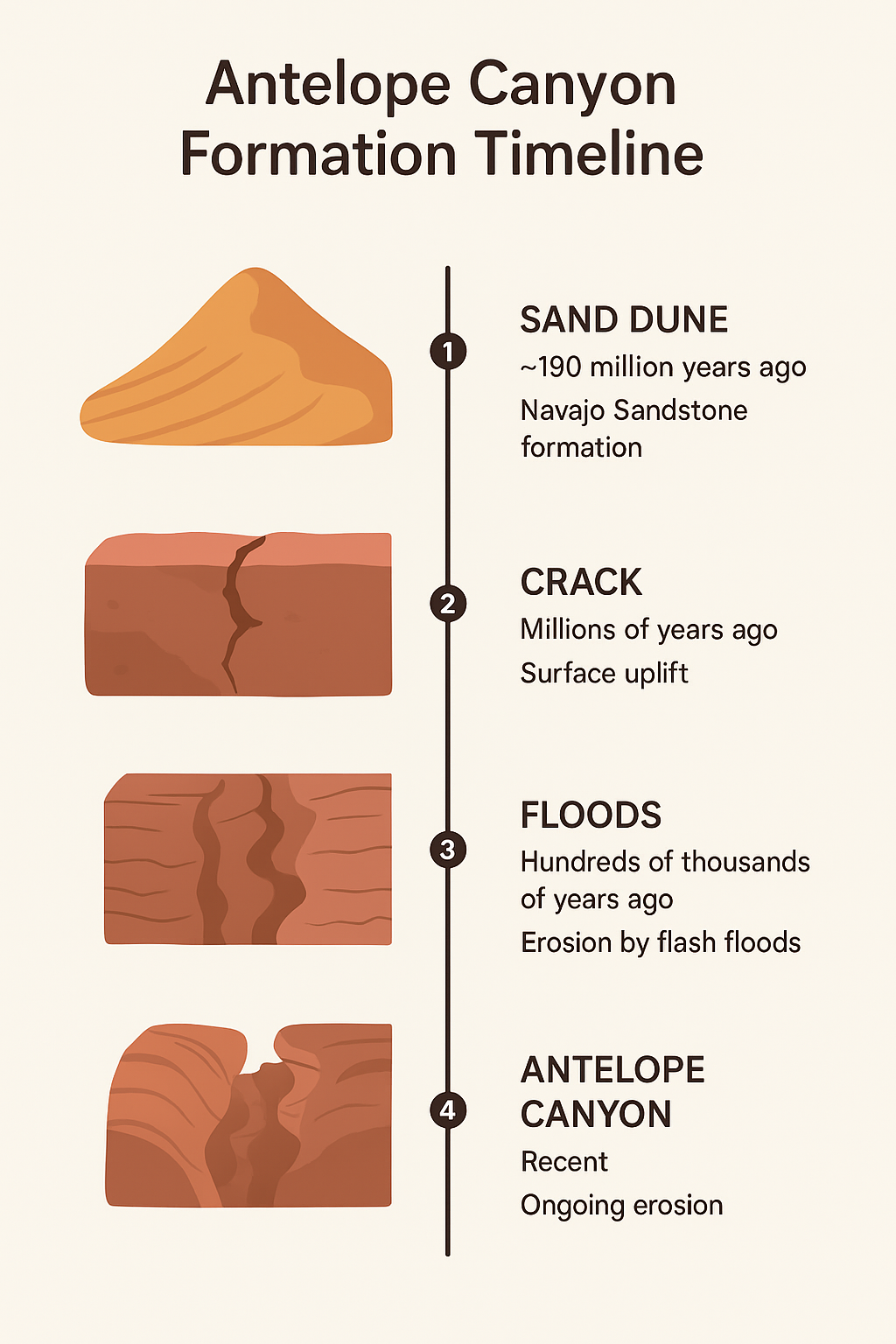

The story of Antelope Canyon unfolds across vast stretches of time:

- Dune Formation (~190 million years ago): The story begins with the deposition of the Navajo Sandstone, vast sand dunes that would one day form the canyon’s foundational rock.

- Crustal Uplift (several million years ago): Geological shifts caused the land to rise, creating fractures and fissures that would guide the flow of water in the future.

- Flood Erosion (from a few million years ago to the present): Flash floods carved deep channels into the sandstone, gradually sculpting the sinuous, flowing corridors that define the canyon today.

- Modern Shape (in the last few thousand years): Even now, seasonal floods continue to refine the canyon’s curves and contours, ensuring that Antelope Canyon remains a dynamic, ever-evolving masterpiece.

Each stage of this process — from sand dunes to shifting water to modern erosion — tells a chapter of Antelope Canyon’s extraordinary geological story, bridging deep time and present-day wonder.

Before we can understand the connection between Antelope Canyon and the Navajo people, we must first look into the Navajo worldview and its Creation Story—the foundation of Diné spirituality.

The Diné Creation Story

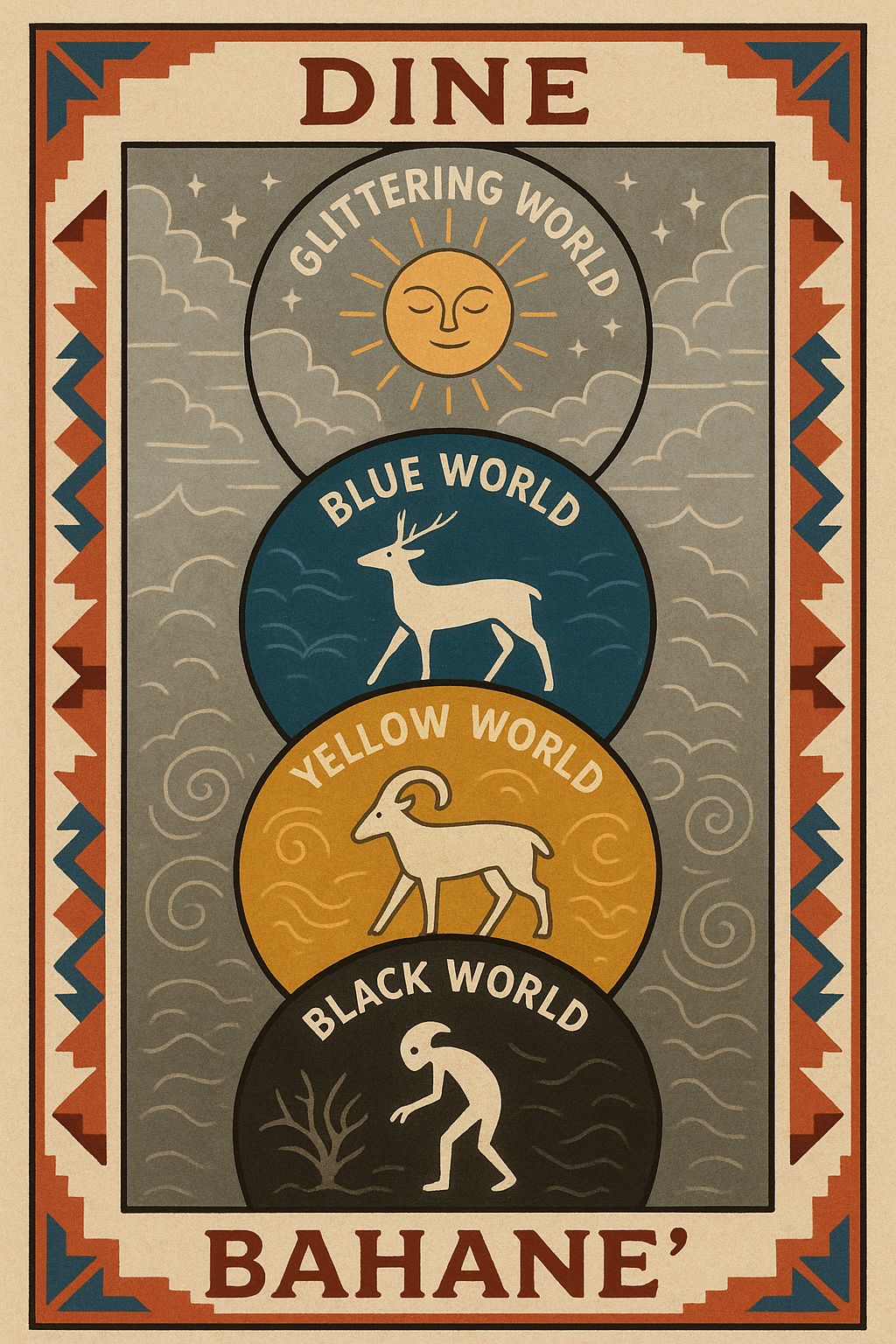

In the Navajo language, the people call themselves Diné, meaning “The People.” They believe that the world was not created in a single act, but evolved through four successive worlds, known collectively as The Four Worlds, until reaching the Fourth World—the Glittering World or White World in which we now live.

According to Diné belief, the universe was born through the passage across four worlds—each representing a step of evolution from chaos to harmony.

The First World, the Black World, was a realm of mist and spirit. From there, the First Beings traveled upward into the Blue World, then into the Yellow World, where conflict and lessons of morality began to shape them. Finally, they emerged into the Glittering World, where the Earth took form and human life began.

This journey mirrors the spiritual path of growth and understanding: a movement from darkness to light, from disorder to Hózhó. It teaches that creation is not a one-time act but an ongoing process of seeking balance with the universe.

The Birth and Meaning of Mother Earth and Father Sky

In the Fourth World, the Holy People gave form to Mother Earth and Father Sky, whose sacred union sustains all life.

Mother Earth

- Symbolism: Land, rivers, plants, animals, femininity, fertility, and protection.

- Origin: In the Fourth World, the Holy People created the Earth and bestowed upon her life and consciousness. The Earth was personified as Mother Earth, the nurturer of all beings and the source of every living thing.

- Symbolic Form:The east stands for dawn, the south for growth, the west for dusk, and the north for rest. Her body is said to be covered with four sacred colors—white, blue, yellow, and black—representing the Four Sacred Mountains.

Father Sky

- Symbolism: The cosmos, stars, sun, moon, time, and universal order.

- Origin: Created at the same moment as Mother Earth by the Holy People, Father Sky represents the power of space and the spiritual realm.

- Relationship: The union of Father Sky and Mother Earth sustains the harmony of the universe—the Earth provides life and nourishment, while the Sky offers light and energy.

Mother Earth is the body that nurtures, the soil beneath every root, and the rhythm of growth that feeds all beings. Father Sky is the breath of stars, the keeper of time, and the giver of light. Their relationship represents the eternal cycle of creation and renewal—female and male, physical and spiritual, earthly and celestial.

Every Navajo ceremony, every chant and sand painting, honors this connection. To live in Hózhó is to live in awareness of the bond between Earth and Sky, between the tangible and the unseen.

Antelope Canyon and Its Connection to Mother Earth

In Navajo (Diné) tradition, Antelope Canyon is far more than a natural wonder—it is regarded as a living part of Mother Earth‘s body. The Diné believe that the Earth is alive and breathing; every rainfall that carves the sandstone and every gust of wind that reshapes the walls is seen as the Earth Spirit breathing. Thus, Antelope Canyon is not “dead rock,” but a Living Earth, animated with sacred energy.

The canyon’s narrow, winding passageways and soft beams of light are seen as the womb of Mother Earth, symbolizing rebirth and purification. To walk through the canyon is to embark on a spiritual journey—a passage from darkness to light, from the unknown to awareness, from nature into renewal.

In Navajo cosmology, water is the source of life, while sandstone represents the bones of the Earth. As water flows through the rock, shaping the canyon, it symbolizes the breath and renewal of Mother Earth. The interplay of light and shadow inside the canyon is viewed as a sacred conversation between Father Sky and Mother Earth—when sunlight pierces through the crevices to touch the ground, it is said to be the kiss of Father Sky, a moment that embodies balance, unity, and the eternal cycle of life.

The Navajo name for Antelope Canyon, Tsé bighánílíní, means “the place where water runs through rock.” Beyond its literal meaning, the name reflects a profound spiritual metaphor: this land carries the spirit of the ancestors and the soul of the Earth itself. For centuries, the canyon was considered a sacred and restricted site.

From Tsé bighánílíní to Antelope Canyon

Discovery and Early Tourism

Before the mid-20th century, Antelope Canyon was known only to the Navajo people and considered a sacred, restricted space.

According to Navajo oral tradition, around 1931, a young Navajo girl named Sue Tsosie was herding sheep when she stumbled upon a narrow fissure in the sandstone that led into what is today known as Upper Antelope Canyon. Mesmerized by the glowing interplay of light and rock, she returned to her community and spoke of the canyon’s hidden beauty. This story, while not exhaustively documented in historical archives, remains a highly significant part of local lore and illustrates how the canyon entered Navajo awareness outside its strictly spiritual context.

During 1950s–1970s, a few explorers and landscape photographers began venturing into the Navajo Nation, capturing images of the slot canyons. Most of these photographs were privately owned, submitted to magazines, or featured in small exhibitions. Though scattered and sparsely documented, these early visual records laid the foundation for Antelope Canyon’s later exposure and recognition in print and media.

By the late 1970s and 1980s, several Navajo families—most notably the Begay family—began guiding small groups of visitors and photographers into the canyon.

These excursions were informal, personal, and often dependent on local permission rather than formal tourism infrastructure.

In Navajo, the canyon is called Tsé bighánílíní. The English name “Antelope Canyon” was given later by non-Navajo settlers or herders, likely because pronghorn antelope once roamed the nearby plains. Naming landscapes after visible animals or natural features was a common practice in the American Southwest.

Global Recognition and Popularity

In the early 1990s, as stunning photographs of the canyon spread worldwide, more travelers came seeking its ethereal light and sculpted walls. From a hidden sacred site to a global landmark, the rise of Antelope Canyon unfolded in three phases:

- Photographic Discovery (1990s): Images published in Arizona Highways and National Geographic introduced the canyon’s surreal beauty to the world.

- The Digital Explosion (2000s–2010s): The rise of digital cameras and social media—especially Instagram—made Antelope Canyon one of the most photographed natural wonders on Earth.

- Cultural Reawakening (Present Day): Visitors increasingly recognize it not just as a geological marvel, but as a sacred embodiment of Mother Earth’s spirit and a symbol of rebirth within Navajo cosmology.

Regulation After Tragedy: Balancing Safety, Tourism, and Sacredness

In 1997, a tragic flash flood in Lower Antelope Canyon resulted in multiple deaths. The event prompted the Navajo Nation to enact stricter safety measures and formalize the guiding system: visitors would require authorized guides, permits, and adherence to regulations.

The tragic flash flood of August 12, 1997 in Lower Antelope Canyon, which claimed the lives of 11 tourists, was indeed a watershed moment in the canyon’s management history.

Prior to that event, many parts of the canyon operated with minimal oversight—wooden ladders, informal guides, and little warning infrastructure.

After the disaster, the Navajo Nation responded by closing access temporarily, redesigning exit routes, installing fixed stairways and safety features, placing alarms and weather warning systems at entrances, and formalizing the requirement that all visitors be escorted by authorized Navajo guides under a permit system.

These measures helped transform Antelope Canyon from loosely managed tourism into a more regulated, safety-conscious, and culturally respectful site.

Current State & Visitor Experience

Today, Antelope Canyon stands as a mature, world-class attraction—carefully managed under Navajo stewardship.

It operates as a Navajo Tribal Park, with all visits guided by authorized Navajo operators.

Each visitor must pay a Navajo permit fee of US $8 per person per day per location, often included in the tour price.

- Tour Duration: Approximately 1 hour 15 minutes (including round-trip transportation)

- Best Visiting Time: 11:00 AM – 1:00 PM (peak light beams, often called the “Light Beam Tour”)

- Transportation: Depart from Page, then ride a Navajo off-road vehicle to the canyon entrance

- Difficulty: Very easy — flat terrain, suitable for all ages

Photography Highlights:

- Iconic light beams at noon (most visible from May to September)

- Soft reflected light creating orange-to-purple gradients on the sandstone walls

- Wind-carved wave-like textures along the canyon curves

Booking Links: Upper Antelope Canyon Tour

- Tour Duration: Approximately 1 hour 30 minutes

- Best Visiting Time: 10:00 AM – 12:00 PM (soft morning light, optimal color layering)

- Transportation: Walk-in access from the visitor center — the entrance is within walking distance

- Difficulty: Moderate — includes metal staircases and narrow passageways

Photography Highlights:

- Layered light and shadow patterns across the canyon walls

- Narrow skylight openings creating dramatic contrasts

- More adventurous and vertical canyon structure

Booking Links: Lower Antelope Canyon Tour

Conclusion

Antelope Canyon’s journey—from hidden Navajo sanctuary to global landmark—tells a story of reverence, resilience, and renewal.

Every beam of light within its walls is a reminder: beauty endures, not only in the rock, but in the people who protect it.